by Catherine Collins

In just 8 inches of clear, salty, not-as-warm-as-you-would-think-for-Australia water, Puck rolled over and speared me with one beady eye.

Puck is a dolphin. This is not a pool or an amusement park, and she is not a captive. No trainer has called her over to me. Yet here she is, inches from my feet, in too-shallow water. Showing off.

Welcome to Monkey Mia, Shark Bay, Western Australia. This is where Puck and her cronies (about eight dolphins most days) regularly swim in to shore to be entertained by the tourists. The dolphins have been doing this since fishermen started feeding them in the 1960s, and though feeding is now illegal (apart from 3 feeds in the morning to specific dolphins, supervised by Department of the Environment and Conservation authorities) the dolphins still show up. Almost every single day.

Because of this incredible habit, they are now one of the most extensively studied dolphin populations in the world. The Shark Bay Dolphin Project reports there are around eighty scientific publications based on Shark Bay bottlenose dolphins to date: and there will be more as research is ongoing.

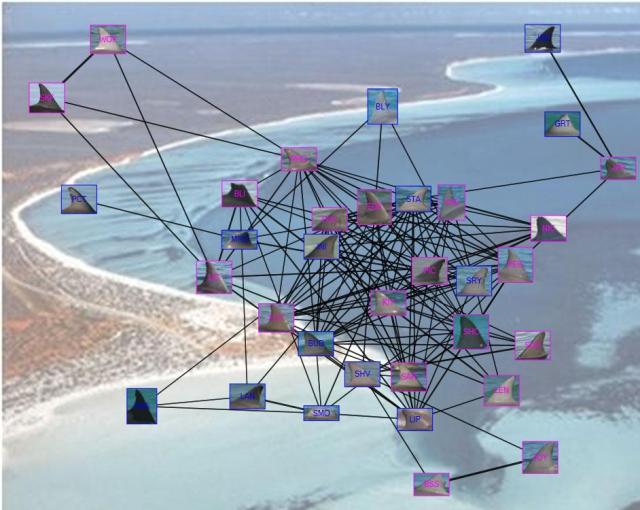

Dolphins are extremely intelligent animals and the research done at Monkey Mia has been vital in unlocking some of the secrets of their complex behaviour and social systems. At Shark Bay, it was discovered that bottlenose dolphins can distinguish between the dolphins that they like and the dolphins that they don’t, and will actively seek out the company of dolphins that they prefer (Gero et al 2005). Other behaviours, such as foraging behaviours, were also discovered here. Dolphins carrying sponges on their noses have been observed at Shark Bay since 1984, and scientists have spent years trying to work out why they do this (Smolker 2001). Suggestions included play, for food, or maybe as a type of camouflage. In 2011, evidence finally emerged which suggested that dolphins like the taste of certain fish that live in the sand. But foraging for these fish damaged the dolphin’s snout, or rostrum, so the dolphins used the sponges to protect themselves. Mother dolphins then taught the technique to their children (Patterson & Mann, 2011).

One of the most important findings in relation to bottlenose dolphins at Shark Bay was the existence of male alliances: strong all-male gangs of 2-3 individuals who do almost everything together (Connor et al 1992). Male cooperation is a rarity in the animal world, so the researchers at Monkey Mia were especially excited about this discovery. Female dolphins just don’t make these kinds of attachments. A girl dolphin is more likely to either get along with many different females, as a social butterfly of sorts, or to have several dolphins which whom she has close ties and spends most of her time. But girls don’t commit to one or two other girls in packs in the same way that the boys do.

Monkey Mia in the Shark Bay Heritage Park is a bit off the beaten track, there’s no doubt about that. Heading down the turn-off by the Overlander truck stop you’ll pass a sign that warns you to make sure you’ve filled your water bottles: because there’s nothing but open road from here on out. Hundreds of tourists make the trip every year, so it must be a million miles away from the sleepy fishing village that it once was, where the fishermen first decided to build a relationship with their local dolphins. This relationship, unknown to them, was to become invaluable to dolphin behavioural research in the coming years, and one of the key reasons why I had to visit.

Late in the evening, my friends and I huddled over hot drinks on the wooden walkways that surround the tourist quarters and lead to the beach. We squirmed in our hoodies, laughing as the sun went down in the distance. Somewhere across the Bay, I thought that I heard a splash. ‘Maybe it’s a dolphin!’ my overactive imagination instantly said. But in Monkey Mia, on any given evening… maybe I was right.

Catherine Collins (@C_Coll89) has a B.Sc in Marine Science and a Graduate Certificate in Marine Biology. She spent half a year in Australia where she got to dive the Great Barrier Reef, swim with manta rays and play with the Monkey Mia dolphins. She is now working towards an MA in Journalism in DCU.

Top image: Dolphins in Monkey Mia, Shark Bay via Catherine Collins

.

References:

Connor, R. C. (1992) Two levels of alliance formation among male bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 89(3), 987-990. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.89.3.987

Gero, S. (2005) Behaviourally specific preferred associations in bottlenose dolphins,Tursiopsspp. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 83(12), 1566-1573. DOI: 10.1139/z05-155

Patterson, Eric M. (2011) The Ecological Conditions That Favor Tool Use and Innovation in Wild Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops sp.). PLoS ONE, 6(7), e22243. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022243

Lusseau D. (2006) Quantifying the influence of sociality on population structure in bottlenose dolphins. The Journal of animal ecology, 75(1), 14-24. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2005.01013.x

Book:

Smolker, R. (2001) To Touch a Wild Dolphin. USA: Anchor Books Random House Publications

Links:

.

Great blog thanks, think I have somewhere new to add to my “bucket list”!

Lol yes definitely Naomi!! It is amazing

As in, I mean Shark Bay is amazing, not the post! Well worth the visit